A recent study shows that both groups took different evolutionary paths to their deeply forked tails.

A warm summer evening is often accompanied by the acrobatic caprices of swifts and swallows. These agile fliers might look alike but they belong to vastly different bird orders that diverged about 85 million years ago. Swallows are songbirds from the order Passeriformes, while swifts are the closest relatives of hummingbirds in the order Apodiformes. The resemblance between these distantly related groups partly relates to their forked tails. But how did this feature evolve in both groups? A recent study in the Journal of Evolutionary Biology collected data for 72 swallow and 39 swift species to tackle this question.

A Common Swift (Apus apus) in Barcelona, Spain. © Pau Artigas | Wikimedia Commons

Selection

To put it bluntly, forked tails can be the outcome of two main evolutionary forces: sexual selection or natural selection. Previous studies have found evidence for both explanations. Male Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica) with deeply forked tails are more successful with female birds, leading to higher reproductive output. This clearly fits the description of a sexually selected trait. However, other researchers have suggested that natural selection could have shaped these tails to ensure more efficient foraging.

In their study, Hasegawa and Arai put forward several predictions to disentangle the effects of sexual and natural selection. Sexual selection predicts that the fork in the tail will look deeper (i.e. the tail feathers look longer). This can be achieved by longer tail feathers (obviously) or by a shorter central tail feather (less obviously). However, a shortening of this central feather could impair flight in species that rely more on tail lift instead of wing lift. Hence, natural selection would select against a shorter central tail in these species.

A Wire-tailed Swallow (Hirundo smithii) feeding a chick ©Manojiritty | Wikimedia Commons

Convergent Evolution

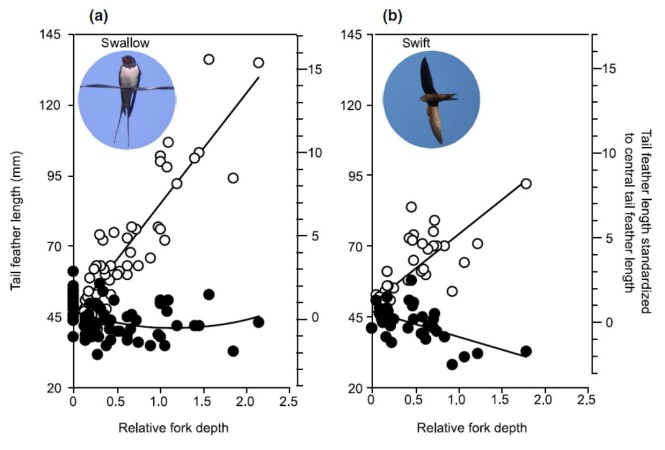

I will not dwell on the technical details – they used a phylogenetic comparative approach – but the results supported a main role for sexual selection in the evolution of forked tails. In both groups, the length of the central tail feather decreased with deeper tails. In swifts, this pattern was linear, while in swallows the relationship was concave (see figure below). This subtle difference is highlighted in the title of the paper: “Fork tails evolved differently in swallows and swifts.”

Moreover, the white spots on some swallow tails gave the impression that the tail is even longer. This optical illusion could relax the sexual selection on the central tail feather. Instead of shortening this feather (and potentially losing aerial maneuverability), swallows just add some white spots to let their tail appear longer. An alluring hypothesis that requires more research.

The central tail feather (black dots) decreased with deeper forks. In swallows, the relationship is concave, whereas in swifts it is linear. From: Hasegawa & Arai (2020) Journal of Evolutionary Biology

Setting the Stage

So, does this study settle the debate: forked tails in swifts and swallows were shaped by sexual selection? You could definitely argue that the recent evolutionary history of this trait was mainly driven by sexual selection. The relationship between tail length and reproductive success is indeed very convincing. However, perhaps these forked tails first evolved in the context of aerial maneuverability and were later co-opted by sexual selection. In other words, natural selection set the stage for sexual selection*.

References

Hasegawa, Masaru, and Emi Arai (2020) Fork tails evolved differently in swallows and swifts. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. Early View.

* This scenario nicely contrasts with the evolution of feathers where sexual selection set the stage of natural selection. You can read more about it in this blog post.