Two genetically distinct subspecies of the Yellow-rumped Tinkerbird sing similar songs, suggesting hybridization.

Want to make a biologist stutter? Just ask him or her to define a species in one sentence. The species problem remains one of the most hotly debated questions in biology. Numerous species concepts have been proposed (Richard Mayden listed no less than 22 different concepts in 1997). Recently, taxonomy has become more pluralistic. Instead of focusing on one species concept, biologists compare different data sources, such as genetic markers, morphology and song characteristics. If all the data lead to the same conclusion, one can confidently draw lines between species. But what if some datasets disagree? For example, the three Redpoll species (genus Acanthis) are morphologically clearly distinct, but have largely undifferentiated genomes. Do you follow morphology (3 species) or genetics (1 species) here?

A Common Redpoll (Acanthis flammea) http://www.allaboutbirds.com/

Speciation

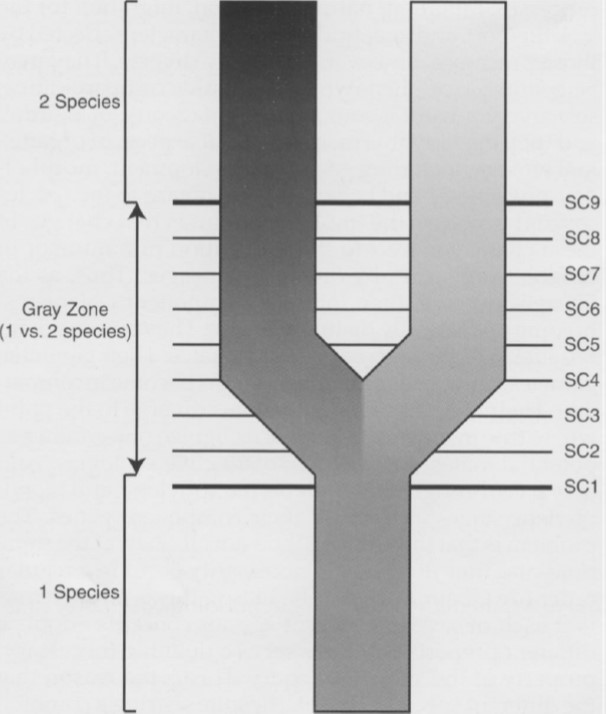

This kind of conundrum is to be expected, given the gradual nature of speciation. Kevin de Quieroz argues that different species concepts correspond to different stages of the speciation process. In some cases, populations might first diverge morphologically, later on followed by genetic divergence (such as the Redpolls). In other cases, it might be the other way around: genetically differentiated populations that look exactly the same (so-called cryptic species). The figure below gives an example of where different species concepts might arise during the origin of new species.

Different species concepts (SC) correspond to different stages during the speciation process (From: de Quieroz 2007).

Tinkerbirds

A recent study, published in Ecology and Evolution, reports a similar situation of disagreement between different species concepts. Emmanuel Nwankwo and his colleagues focused on three subspecies of the Yellow-rumped Tinkerbird (Pogoniulus bilineatus). They showed that the subspecies conciliator (from the Eastern Arc Mountains in Tanzania and Kenya) is genetically distinct from the Tanzanian subspecies bilineatus. However, both subspecies sing similar songs, suggesting that they might interbreed. In addition, a third subspecies (fischeri from Kenya and Zanzibar) is genetically closer to bilineatus, but sings a completely different song. In summary, there is discordance between genetic data and song characteristics.

Although this study presents an interesting case, it misses one crucial piece of evidence: hybridization. The similar songs of bilineatus and fischeri only suggest interbreeding. The authors don’t provide any evidence for actual interbreeding. Perhaps these subspecies sing similar songs to guard their territories, but use other cues in mate choice. Or, if they do interbreed, hybrid offspring might be inviable due to genetic incompatibilities. In either case, song might not contribute to hybridization and becomes irrelevant in species delimitation. But before we jump to premature conclusions, let’s study these fascinating birds some more.

Yellow-rumped Tinkerbird (Pogoniulus bilineatus). From: http://www.hbw.com/

References

De Queiroz, K. (2007). Species concepts and species delimitation. Systematic biology 56, 879-886.

Mason, N. A. & Taylor, S. A. (2015). Differentially expressed genes match bill morphology and plumage despite largely undifferentiated genomes in a Holarctic songbird. Molecular Ecology 24, 3009-3025.

Mayden, R. L. (1997). A hierarchy of species concepts: the denouement in the saga of the species problem. In Species: The units of diversity (ed. M. F. Claridge, H. A. Dawah and M. R. Wilson), pp. 381-423. Chapman and Hall, London.

Nwankwo, E. C., Pallari, C. T., Hadjioannou, L., Ioannou, A., Mulwa, R. K. & Kirschel, A. N. (2017). Rapid song divergence leads to discordance between genetic distance and phenotypic characters important in reproductive isolation. Ecology and Evolution.

This paper has been added to the Piciformes page.