A recent study compared the genetic make-up of migratory and resident populations across North America.

In January 2016 I attended the Plant and Animal Genomics (PAG) meeting in San Diego. Obviously, I took some time off for bird watching and managed to add some new species to my life-list, including the Ruby-crowned Kinglet (Regulus calendula). However, this blog post will not focus on this red-capped beauty, but on a related species: the Golden-crowned Kinglet (R. satrapa). This small songbirds has a wide distribution across North America and displays an interesting behavior: populations in the center of the range migrate while the peripheral populations (on the east and west coast) are resident.

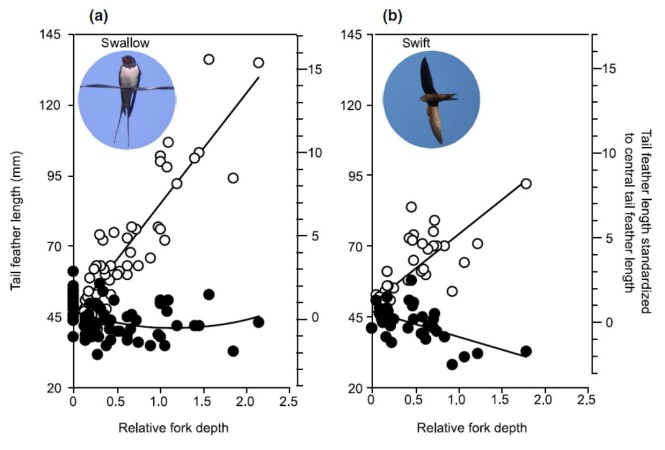

This situation provides ideal circumstances to study the effect of migratory behavior on genetic differentiation and diversity. Resident behavior is expected to reduce gene flow between populations, resulting in more genetic differentiation. In addition, the reduction in gene flow might increase the influence of genetic drift in isolated populations, which leads to loss of genetic diversity. Migratory behavior, on the other hand, will increase levels of gene flow, culminating in less genetic differentiation and more genetic diversity. A recent study in the Journal of Ornithology tested these predictions.

A Golden-crowned Kinglet in Washington © Francesco Veronesi | Wikimedia Commons

East and West

The researchers used seven microsatellites to probe the genetic make-up of migratory and resident populations of Golden-crowned Kinglets across North America. These genetic markers revealed a clear separation between eastern and western populations (in accordance with a previous study). This geographical pattern is probably a genetic signature of the Last Glacial Maximum when eastern and western populations of Golden-crowned Kinglets were isolated in distinct refugia. The population in Alberta showed some signs of admixture and could be a potential bridge for gene flow between east and west.

But what about migratory and resident populations? The authors start their discussion with the following statement: “We found no evidence to support our hypothesis that migratory behaviour influences neutral genetic differentiation and neutral genetic diversity for Golden-crowned Kinglets.” Indeed, there was no significant difference in genetic differentiation or diversity between migratory and resident populations.

There was no significant difference in genetic differentiation between migratory and resident populations of the Golden-crowned Kinglet. From: Graham et al. (2020) Journal of Ornithology

Genomics

It thus seems that the genetic population structure of these passerines is mainly determined by the glacial dynamics of the Pleistocene. Does this mean that migratory behavior has no effect on genetic patterns? Not necessarily, there are several explanations for this result. First, the resident and migratory behaviors might be a recent development that has not yet impacted the genetic make-up of these populations. Second, the genetic markers in this study (seven microsatellites) might be too variable to pick up subtle differences between resident and migratory populations. Moreover, the genetic variants associated with migratory behavior might be restricted to particular genomic regions, such as in warblers (see here and here). A genomic approach is warranted.

References

Graham, B. A., Carpenter, A. M., Friesen, V. L., & Burg, T. M. (2020). A comparison of neutral genetic differentiation and genetic diversity among migratory and resident populations of Golden-crowned-Kinglets (Regulus satrapa). Journal of Ornithology, 1-11.