Two owl subspecies might be the outcome of a peculiar speciation model.

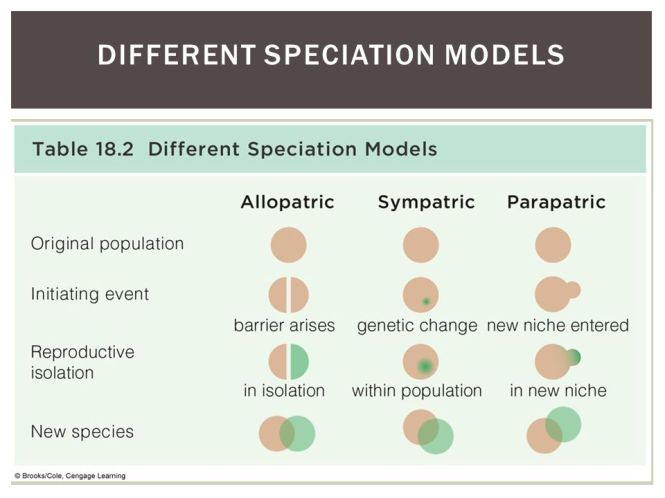

Open a standard textbook on the origin of new species and you will probably come across three main speciation models: allopatric, sympatric and parapatric speciation. In short, allopatric speciation occurs when two populations become geographically isolated leading to a sudden break in gene flow. Over time these populations diverge genetically into different species. Alternatively, during sympatric speciation, populations diverge even though they live in the same habitat. Parapatric speciation, finally, entails the differentiation of two neighbouring populations that still exchange some genes in the process.

Three different speciation models in a standard textbook.

Mixing the Models

Besides this Mayrian triumvirate (as German biologist Ernst Mayr popularized these models), several other modes of speciation are possible. One of these is heteropatric speciation, in which populations occur in the same area at some times during the year, but are geographically separated at other times (in a sense a hybrid between allopatric and sympatric speciation). This model nicely applies to birds where one population is migratory while the other is sedentary. You can read Kevin Winkers’ excellent review on this process in Ornithological Monographs.

The Origin of Owl Subspecies

Two subspecies of the Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius acadicus) might have diverged in a heteropatric fashion. One subspecies brooksi remains sedentary on the island of Haida Gwaii (British Columbia) while the other subspecies acadicus is migratory. During fall and winter both subspecies co-occur, but during the rest of the year they are far apart. Are they still interbreeding and exchanging genes when they meet?

To figure this out, Jack Withrow, Spencer Sealy and – not surprisingly – Kevin Winker sequenced mitochondrial and nuclear DNA (AFLPs) from both subspecies. The analyses revealed that the subspecies are genetically differentiated with extremely low levels of gene flow. In fact, it seems likely that there is no gene flow at all (a genomic approach is necessary to be sure).

A Northern Saw-whet Owl (from http://www.hwb.com)

Ice Ages

Nonetheless, the most plausible scenario is that an ancestral acadicus population colonized the Haida Gwaii about 16,000 years ago when this island was a refugium during the ice ages. This population became sedentary (and who could blame them, wouldn’t you like to live on an island?) and started diverging from the migratory mainland population. A nice example of heteropatric speciation?

References

Withrow, J. J., S. G. Sealy and K. Winker (2014). Genetics of divergence in the Northern Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius acadicus). The Auk 131(1): 73-85.

The paper paper has been added to the Strigiformes page.

[…] than one year ago (in January 2018 to be precise), I wrote a blog post about the evolutionary history of the Northern Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius acadicus). A genetic study […]

[…] not only of interest to the question of multispecies hybridization, they are also relevant for the heteropatric speciation scenario. This model applies to populations that occur in the same area at some times during the […]